This is the second post in a six post series about the Gambaga witch camps in Northern Ghana.

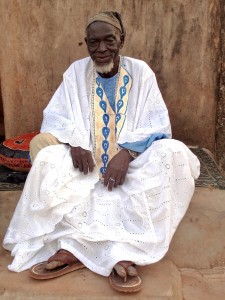

The Gambaranna

The going rate to interview a witch is 1 Cedi (approximately $.67), so I make sure to fill my pockets with small bills before approaching the camp.  When I enter, I kneel and clap twice to pay tribute to the Gambarrana.  He is a Muslim and dressed in a long white flowing robe with blue trim.  He inquires of my purpose, and Simon translates to him that I am an American journalist working in Ghana and interested in writing about the witch camps.  Simon has told me the Gambarrana is skittish about providing access to journalists, as previously reporters have been critical of the conditions of the camp.  I assure him that I have heard many good things about his efforts and then supplement the statement by slipping 5 Cedi’s under his rug–as Simon had suggested.  He nods and we stroll inside.

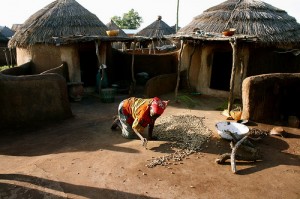

The compound is made  of a number of small, circular-shaped huts that face each other in groups of five or six.  They have dirt floors and no water or electricity.  When I arrive, the women have just returned from the field and are scattered about, mostly sitting on the ground or tiny footstools.  In the middle is a large pile of peanuts that they sift through, occasionally taking a handful to munch on.

An accused witch in Gambaga arranges nuts (photo by Brian McAndrew)

The women’s faces are weathered, their shoulders slumped, and they appear torn between two  forces: the survival impulse that drives them to push on and the anguish of their plight, which has caused them to be banished–under the threat of violence and even death–from their friends, families and homes.

The first interview I conduct is with Kondug Dute.  Approximately sixty years old, she arrived in Gambaga from her village ten years prior, after being accused of bewitching a child who had died.  Inexplicable deaths–especially among the young–are one of the most frequent motivators for allegations of witchcraft, and Dute was accused by the  son of a rival.  She was chased from the village amidst threats of violence and now lives in Gambaga selling firewood.  “I have been disgraced and separated from my family, yet I have done nothing,†Dute tells me.  Like most of the women I interview, Dute says that she is innocent of all allegations of witchcraft.  However, Dute and others do not deny that witchcraft exists.  When I ask one woman if she believes that her peers might be witches, she tells me flatly:  “There’s no way I can know that; it’s between them and God.â€

My first interview in Gambaga (Photo by Brian McAndrew)

I interview four women that evening and all of their stories are similar.  Most have been accused after a death in the village, others simply because a rival said they were “haunting them†in their dreams.

It is rare that there is any fact-finding effort in regard to the allegations facing an accused witch. The only possible vindication occurs during a trial by ordeal that is sometimes held at the witch camp.  In these cases, a woman slaughters a fowl in the presence of the Gambarrana and other spiritual leaders.  If the fowl dies with its wings facing upward, the woman is exonerated.  According to Simon, this happens on average 20% of the time, but even if a woman is found not guilty she will still often stay at Gambaga.  One woman, who had won her trial, tells me that the stigma associated with witchcraft is so great that she was unable to return to her home regardless of her “acquittal.â€

The women tell me that their biggest problems are a lack of food and basic healthcare.  They look emaciated and the few children milling about appear even worse.  One lays motionless on the ground the entire time I am conducting interviews.  It is naked and a horde of flies congregate around its buttocks.  For the initial twenty minutes, no one attends to it, despite the fact that it moans on and off.  I grow more and more disturbed by its presence and finally one of the women notices my discomfort and carries it to another part of the compound.  “It has a sickness in the rectum,†Simon says.

I pay the women and they thank me and insist that I take handfuls of peanuts.  It is just a bit after seven when I leave the compound, but there isn’t a single restaurant open anywhere.  I buy two packages of biscuits and head back to Martha’s. There I take a shower, pouring three buckets of cold water over my head.  I go out to look for a beer and find one and a few drinking partners as well.  I want to know if they believe that the women of Gambaga are actually witches, so after a drink I summon the nerve to ask them.

“Of course,†they say.  “Why else would they be here?â€

Read the first post in this series or check out pictures of Gambaga in the photo  gallery.

Leave a Reply